June 4, 2013

By Duy Hoang, Angelina Huynh, and Trinh Nguyen

INTRODUCTON

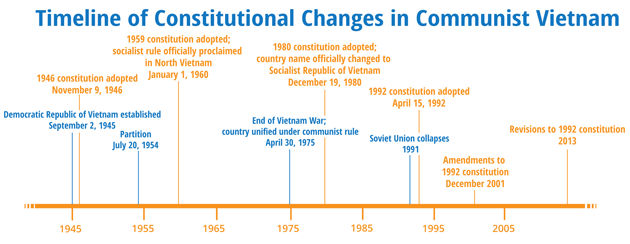

The Vietnamese Communist Party has a lot riding on its project to renew the country’s constitution. Beset by political and economic stagnation, the communist leadership launched a constitution revision process in January 2013 as a means to shore up popular support and increase the state’s relevance. Communist Vietnam has gone through four constitutions since its founding. The latest version was adopted in 1992, with minor amendments approved in 2001.

To show popular support for the current constitutional proposal, party and government leaders have cited a host of statistics indicating civic engagement. In late March, National Assembly Chairman Nguyen Sinh Hung claimed that 20 million comments had already been received and mostly in support of the government’s constitutional draft. “This shows that the people are the masters of important national issues,” he declared.

Nguyen Sinh Hung’s boast and the upbeat coverage in state media has sparked debate on social media platforms as Vietnamese netizens question whether their compatriots have really been that involved in the revision process. Although authorities have called on citizens to provide comments, they have intimidated critics and labeled suggestions for fundamental change as “anti-Party” or “exhibiting moral decline.”

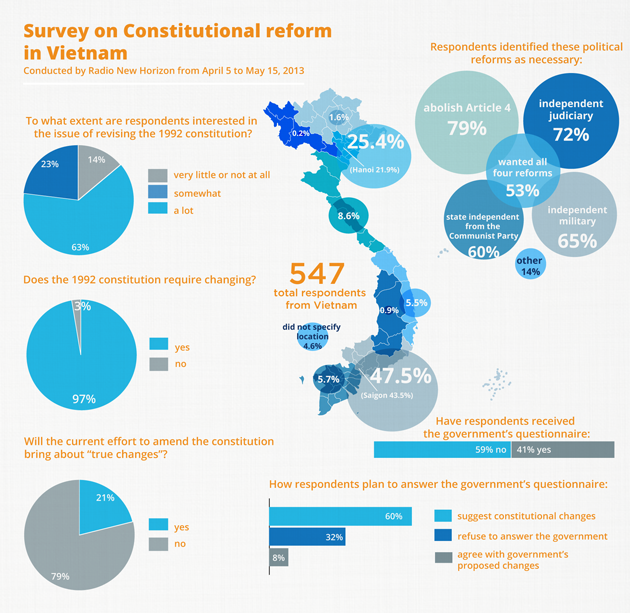

A recent online poll conducted by Radio New Horizon, a citizen journalism platform supported by Viet Tan, found that popular reaction to the constitutional revision has decidedly been mix. According to this survey, Vietnamese people are following the constitutional issue, but to varying degrees. While nearly all respondents indicated that the constitution required changing, 80% of respondents did not feel that they could freely provide input to the government.

To the extent that this survey reflects the general sentiment of the Vietnamese public, the Hanoi regime will have difficulty convincing the populace that this is a relevant and legitimate political exercise. Ultimately, ambivalence regarding constitutional reform is as much a referendum on the Vietnamese Communist Party as it is on the legal document.

KEY FINDINGS FROM THE SURVEY

Radio New Horizon’s online survey on reforming the 1992 constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was conducted over a six week period from April 5 to May 15, 2013. Almost a thousand individuals participated through Radio New Horizon’s blog and Facebook page. Although the survey garnered responses from Vietnamese living inside and outside the country, the results herein only include the 547 responses from inside Vietnam.

Though not an entirely random sample of the country’s entire population, we believe the respondents are reflective of the sizeable number of Vietnamese who are active online and relatively attuned to political issues. Based on their self-identification, the majority of participants are currently living in Hanoi or Saigon.

The main findings of the survey are:

- Interest in constitutional reform is relatively high

Participants were asked to what extent they are interested in the issue of revising the constitution: 63% responded “a lot,” 23% said “somewhat,” and 14% indicated “very little or not at all.”

- There is a consensus that the 1992 constitution requires fundamental changes

When asked whether the constitution required changing: 97% said “yes” and 3% responded “no.”

To learn what needs changing, participants were asked their opinion on a list of potential reforms from which they could select more than one choice. They selected the following reforms in order of popularity:

![]() 79% wanted to abolish Article 4 of the constitution which grants the Communist Party a monopoly on power.

79% wanted to abolish Article 4 of the constitution which grants the Communist Party a monopoly on power.

![]() 72% wanted the judiciary to be independent from the government and Communist Party.

72% wanted the judiciary to be independent from the government and Communist Party.

![]() 65% wanted to make the military independent from the Communist Party.

65% wanted to make the military independent from the Communist Party.

![]() 60% wanted the state to be independent from the Communist Party.

60% wanted the state to be independent from the Communist Party.

![]() And 53% of respondents chose all four reforms above.

And 53% of respondents chose all four reforms above.

The two choices of abolishing Article 4 and establishing judiciary independence reflect people’s wishes for more political space and a rule of law. In fact, these two issues have been dominating the current online debate on constitutional reform.

- The Communist Party and Government’s solicitation for public commenting is unlikely to garner uncensored input

In addition to meetings organized by party and government bodies, one of the official means for soliciting public comments has been through questionnaires distributed to households. 41% of our survey’s respondents said they received the government questionnaire regarding the constitutional proposal while 59% said they had not.

When asked how they intend to answer the questionnaire, 60% of respondents said they would suggest constitutional changes, 32% said they would refuse to answer, and 8% said they would agree with the government’s proposed draft in its entirety. From this question, it is worth noting that nearly a third of respondents (32%) indicated they would effectively boycott the commenting process.

Furthermore, 80% responded that they did not “feel free to express their true feelings” while 20% said that they did feel free to answer truthfully.

- Ultimately, there is significant skepticism in the Communist Party’s proposal to reform the constitution

When asked whether they thought the current effort to amend the constitution would bring about “true changes,” 79% of respondents said “no” and only 21% indicated “yes.” This last question perhaps sums up the distrust that many Vietnamese have for the regime’s reform promises.  A BRIEF CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY

A BRIEF CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY

Communist Vietnam has undergone three major constitutional changes since its 1946 founding document—each period coinciding with significant political and social upheaval. The western-style 1946 Constitution established the newly formed government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with democratic trappings in an effort to solidify national unity against French colonialism. While the 1946 constitution provided guarantees for freedom of speech, assembly and the press, it was never meant to be carried out, foreshadowing and cementing the practice of nominally enshrining political and civil rights.

Against the backdrop of the country’s partition in 1954, the 1959 Constitution abrogated democratic ideals in the favor of communist dogma and officially established socialist rule in North Vietnam.

Drafted after the country’s reunification and at the apex of the communist bloc’s power, the 1980 constitution became the ideological roadmap for a modern socialist state and the authoritarian practice of interpreting laws through the party’s lens. The official name of the country was changed to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

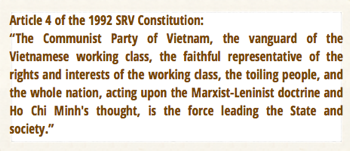

One of the key provisions of the 1980 constitution established political power as resting with the Communist Party itself, as stipulated in Article 4. Human rights were first mentioned in the third draft of the 1980 constitution and was broadly interpreted as being manifested as “citizen rights.”

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Hanoi regime renovated its socialist doctrine through the 1992 constitution to simultaneously restructure the economy and block political pluralism. While the 1992 constitution repealed the party’s direct control over socioeconomic affairs, it maintained Article 4 with only a slight wording change. The 1992 constitution also defined “human rights [as] respected…and determined by the Constitution and the law”—a qualifying phrase allowing authorities to simultaneously claim tolerance for human rights while allowing for detention of supposed lawbreakers.

In an effort to show openness, the drafting of the 1992 constitution was complemented by the solicitation of feedback through meetings organized by party cells. Final amendments to the 1992 constitution took place in 2001 and again included public commenting through bureaucratic processes.  THE 2013 CONSTITUTIONAL DEBATE

THE 2013 CONSTITUTIONAL DEBATE

The National Assembly debated the first draft of the latest constitutional revision in the fall of 2012 and the document was released for public comment between January and March 2013. Perhaps surprised by the level of public debate and facing internal fissures within the party leadership, the National Assembly extended the time period for public opinion until September. In October, the National Assembly is scheduled to vote on adopting the draft constitution.

Whereas the 2001 amendments to the 1992 constitution occurred during the dark ages of Internet penetration in Vietnam, the public discourse this time has been fueled by online forums and social networks. Skipping the official commenting process, thousands of Vietnamese have publicly supported grassroots campaigns calling for fundamental constitutional changes.

In particular, the emergence of an alternative constitution in mid-January has garnered widespread attention. Named after a group of 72 intellectuals (including many well-known party figures), Petition 72 consists of a seven-point proposal for constitutional reform along with a totally revamped constitution. To date, 15,000 people have signed on to Petition 72. Their names are listed on the activist website www.boxitvn.net.

Two other efforts have also received significant support: an open letter by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Vietnam and an online petition named “We – the Free Citizens” (Chung ta – Cong Dan Tu Do). These efforts reflect the sentiment among many of Vietnam’s Catholics and bloggers, two of the country’s most influential activist communities.

The unifying theme among all the above petitions is the demand to repeal Article 4, which grants the Communist Party monopoly rule. The continued existence of Article 4 is a constant contradiction for the regime. Without Article 4, the Communist Party would face legalized political opposition and some form of multi-party democracy. By retaining Article 4, the Communist Party undermines basic notions of constitutionalism and rule of law.

The unifying theme among all the above petitions is the demand to repeal Article 4, which grants the Communist Party monopoly rule. The continued existence of Article 4 is a constant contradiction for the regime. Without Article 4, the Communist Party would face legalized political opposition and some form of multi-party democracy. By retaining Article 4, the Communist Party undermines basic notions of constitutionalism and rule of law.

In a televised speech on state media in late February, party general secretary Nguyen Phu Trong denounced those who championed the abolition of Article 4, citing such reformist ideas as a “deterioration of the country’s morals and ethics.”

Le Hong Anh, Minister of Public Security, was even more blunt: “As we receive input from citizens, we must ensure the central and unified leadership of the Party.” He warned against letting people “abuse democracy to sabotage the party and state.

Critics have been swiftly punished. Nguyen Dac Kien, a journalist for the state-run Family and Society newspaper, was fired less than 24 hours after penning an essay critical of Nguyen Phu Trong’s remarks.

In an interview with Radio Free Asia, Nguyen Dac Kien explained: “My awareness of citizen’s rights did not come yesterday or the day before—it has been a long process. The motivation to express that awareness came after listening to what [Trong] said on television.” He added, if communist leaders “want to keep Article 4, maintain your leadership, politicize the military, and do not want pluralism or separation of powers, then it is your own wish and your Party’s. You can’t assume that is the wish of the Vietnamese people.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Results from the Radio New Horizon survey underscore the deep scepticism among many Vietnamese that the Communist Party is sincere in wanting to reform the constitution. This scepticism is confirmed by the comments of senior communist leaders and the draft proposal itself.

In its analysis of the draft constitution, the human rights organization ARTICLE 19 voiced serious concerns that the proposed amendments allowed for broad restrictions to freedom of expression, assembly, and association. Particularly, ARTICLE 19 noted that new amendments could further erode fundamental rights, instead of protecting them. ARTICLE 19 recommended language on human rights to meet international standards.

In the coming months, grassroots efforts to advocate for genuine political reforms will undoubtedly persist. By ignoring or repressing these voices, the Vietnamese Communist Party is showing why the project to renew its political support through constitutional reform is likely to fail.

Human rights attorney Le Quoc Quan, writing for the BBC the week before his arrest on December 27, 2012, summed it up: “the constitution cannot be a political charter belonging just to a ruling political party because by its nature the constitution must provide a level playing field for diversity and progress.”